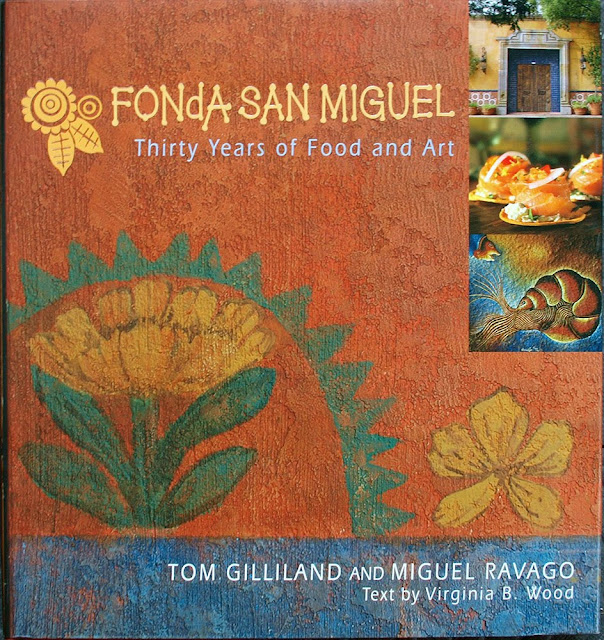

This book came out in 2005 and it's now a collector's item. I saw it on Amazon.com listed new for over $1,000. Amazing.

Fonda San Miguel is one of those restaurants that just gets better and better. Its cuisine is all about interior Mexican meets haute cuisine. Amazing stuff. And really wonderful collections of art all over the walls. The walls themselves are the result of two years of custom mural painting by a well regarded, Mexico City based mural painter. Everything about the restaurant is exciting and artful.

I've documented the art, the murals and the decor at the restaurant for nearly a decade. In 2005 the owner, Tom Gilliland, decided to do a book. The actual food shots were done by San Antonio food specialist, Tracy Mauer. The rest of the art is from my collection. In 2006 the book won international awards for design.

Ben, Belinda and I had dinner there last Saturday night. The house was packed. The line for valet parking stretched down the street for half a block. Every spot in the bar and lounge areas was filled. Bright drinks and bottles of wine floated around on waiter's trays like a fast motion scene from a movie.

The wait for walk-ins was around two hours. The smart people made reservations a week or two in advance. Recession? Not here.

We had a great meal. The little things make a difference. Hand made tortillas. Perfect Pork Conchinita. Well crafted Mojitos. A mellow and satisfying Chili Relleño. A professional waiter with real charm. I watched the staff work. Every diner felt special.

Fun to have done this project. Even more fun to know that we'll be back time and time again. Not just for the food but also to watch the ever changing show of art on the walls.

If you come to Austin you might want to make time to try this place. Call ahead for reservations. Weekends? Call way ahead.

2.21.2012

2.20.2012

Spirited Nonsense and Neutral Reality.

The camera on the left is a Panasonic G3. It features 16 megapixels of resolution, pretty clean files up to 1600 ISO and it weighs next to nothing. The lens on the front of the camera is very sharp and has beautiful tonality. The camera on the right is a Canon 1DS Mk2. If features 16 megapixels of resolution, pretty clean files up to 1600 ISO and it weighs a ton. The lens on the front is a Zeiss ZE 85 mm 1.4. It's sharp once it's stopped down one and half stops and it has beautiful tonality.

The camera on the left cost me $550. The camera on the right originally retailed for $ 8,000 but I bought it well used, in the middle of last year for $1,800. There are differences between these cameras and similarities. They both turn out really nice files and the files look really nice on my monitors.

If we use our knowledge base from 2005 and earlier then the one on the right is the camera to have. But if we are open minded, cognizant of market changes and willing to make a go at understanding the impact of technological development, the camera on the left can be compellingly argued for.

I just read two different discussion threads on a global photography website. One thread praised the advances in cellphone cameras and noted that a flood of images from citizen cellphone-o-graphers is supplanting traditional photojournalists around the world in supplying content for news oriented websites, magazines and newspapers. The gist of the article was that the 8 megapixel files from the cellphone are acceptable to editors far and wide. The argument is that once a certain technical threshold is crossed the content trumps the device with which it was captured. I'll buy that. So, the new professional in the field of photo-journalism is the guy or girl who is in the right place at the right time with the minimally acceptable or better equipment. Access being the prime feature. In one camp the prevailing thought among amateurs and hobbyists is the vindication of their talents by the eradication of a profession and its replacement by free operators. And it's all made possible through the de-evolution of technical necessities. Pixel content is less rigorous than printed content. And more forgiving which lowers the barriers to entry while sheer quantity allows the editors and art buyers to crowd source their way to competence.

The other, opposite argument I read concerned what constitutes bare minimum necessities in a "professional" camera. The unwashed majority vociferously insisting that no one, NO ONE could be deemed a "pro" unless they were equipped with a camera that outperformed all previous cameras in the history of modern, digital photography. The camera would have to shoot at high frame rates, focus in the dark, see in the dark, withstand nuclear blasts, electro-motive pulses and as much rain and mud as you could possibly throw at it. The pro camera would yield files as smooth as ISO 64 film from an 8x10 view camera but it would do so at 25,000 ISO. In their world all pros shoot with enormously long and complex lenses. They must have, at a minimum, lenses at 300, 400 and 600mm that open up to f2.8 in order to put "cluttered" backgrounds out of focus. All zooms should be f2.8 or faster. No professional work could conceivably be done with anything less than a full frame sensor. And not just any sensor but whatever tomorrow's sensor is, today.

The later camp compiles their information based on what they read in magazines about photographers who seem to all have contracts with Sports Illustrated. The first camp seem to derive their information from the legions of starving pros who are trying to "own" the mobile niche of telephone photography in order to sell gee-gaws, lectures and software packages. "Actions!!!!!" Even the word feels like we're all moving the game forward....

So, what's the reality? I'm thinking it falls in between and also lives with the outliers. Paul shoots his architectural stuff with medium format cameras and incredibly expensive optics from the Black Forest and the mountains of Switzerland. I shot books today for a very large corporation using a nice little micro four thirds camera. We're finally living in a time that gives truth to so many of the mythological sayings that have been dreamed up in the service of explaining photography. "Horses for courses." (which I hate) means you get to choose precisely the best equipment for your task as Paul does. "It ain't the arrow it's the indian...." (equally offensive) is the tactic I pressed into service today. The final destination for my images will be the corporation's website. The camera was less important than the lighting, the angles and the post production. Perhaps we could have even shot this one with an iPhone given total control over the lighting and aperture.....

With the emphasis shifted to post processing and to web use the truisms about what constitutes professional gear are rendered silly and anachronistic. The knowledge, taste and point of view are important. The brand or size of camera are much less so.

Given the use by my client of the final images today the camera I reached for was a micro four thirds camera with the stunning 45mm 1.8 Olympus lens (although the 40mm 1.4 would have been equally good......). The full frame camera I used on the last go around was not as successful. Why? because we were working close but with a longer lens and the depth of field was a critical aspect. When shooting a book it's usually important to keep the entire product in focus even though you are shooting at an angle to show dimension. The smaller format with the shorter focal length delivered a more convincingly sharp file that required less work than its full frame cousin.

Tomorrow I have a portrait shoot that will require very narrow depth of field and the smoothness that comes from lots of detail. I'll use a full frame camera for that. But I could probably make an equally good photo with a fast, long lens on the smaller format if I toss in some time for post processing.

The bottom line is that no one outside the field, or even outside your business, really knows what the hells is going on. If you are basing your business plans as a photographer on what you read on forums you are pretty much doomed to failure. You might make a unique selling proposition out of the flexibility and portability of smaller cameras. You might have a style that depends on a larger format camera and it may be a style that appeals to an affluent niche.

But it's never a good idea to try and fit all of the pegs into a single round hole. It never works out well.

Right now my money is on the smaller cameras. They lower the barrier to entry, deliver proficient and efficient results and they require so little investment that they become disposable. That lowers the momentum to resist change when paradigm shifting technology innovations destroy existing markets. And they are more fun to tote. But, being conservative, I'll hedge my bets by keeping my premium, full frame cameras and prestige lenses handy. Handy but probably undisturbed...

I've been writing about small cameras for nearly three years now. I think the things we've discussed here are starting to come to market fruition. I know the smaller gear is demanding more and more of my mindshare. What about you?

A small camera I've been playing with. Yesterday. Panasonic G3. The pre-OM-D.

Tiny, Light, Fast, Detailed, Sharp, Quiet, Compact and Cute. 90% of the way there. Olympus did a great job with their PR for the upcoming OM-D camera. Everyone I know who has an interest in mirrorless cameras is talking about it, saving up their money to buy one and rushing to get themselves on a list. And who can blame them? It looks like everything we've pined for over the last few years. Not to mention that the whole mirrorless m4:3 universe now has some powerhouse lenses as booster rockets for our insatiable imaging. In some camps the OM-D is starting to sound a bit like the second coming of the camera industry. But here I go again: The relentless contrarian.

The bottom line? I don't know that there is a bottom line. The camera world is a chaotic place with little camps swirling around banners. In one corner we have the full frame 35mm high res contingent for whom everything hinges on ultimate resolution and sharpness. We have, of course, our micro four thirds camp where we look to blend high performance with high usability and high portability (after all, what good is all the gear if it's too cumbersome to carry?). We have the pilgrims of nose bleed performance who have knotted the ropes of high intention around their photo vest frocks and set out into the desert in pursuit of the mysteries of medium format, and we have the legions of people traipsing around willy-nilly with their iPhones snapping a glorious quantity of interesting frames and then shoving them through the kaleidoscopic blender to make them more.....appealing.

I've been beaten over the head with the idea that there is no "right or wrong." That all approaches are worthy and equal. That there's an equivalence of sorts whether you use an 8x10 inch film camera or your happy-snappy phone to create your images. While I tend to veer toward a more defined philosophy where effort has value and is integral to the process I won't confuse things by arguing that today.

Where I will comment is on the performance of Olympus' promotional machinery. Well done, marketers. In a short amount of time you created a tremendous amount of buzz, filed us with desire we barely knew we had, deflected our attention away from similar products and got us all excited. If the product they deliver does everything they say it will be a monumental success, and, no doubt, it will be a hell of a lot of fun to shoot with.

The G3 is no OM-D but it's a hell of a lot closer than a lot of people might like to believe. I think I'll go out and shoot with mine again today. After all, it's already in my hands.

While I researched the OM-D I came across a camera that sounds eerily like the camera we've all been waiting for....only it's been on the market since June of 2011. It has the following specs: Fastest focus in all of m4:3rds (arguably), The best 16 megapixel sensor in all of m4:3rds as stated by DPReview and DXO. A built-in 1.4 megapixel EVF finder. A swivelling, large rear LCD panel. And a brilliantly implemented touch screen interface. OMG did they launch the OM-D early and not tell anyone till a few weeks ago??? No, it turns out that Panasonic has been building and delivering this camera for the better part of a year. It's called a G3. But for some reason no one seems to care. Except the Panasonic users who are currently hoarding them and shooting them. There are only two features that the G3 doesn't deliver that are on the OM-D checkboxes: Full Navy Seal weatherproofing (for all you rugged types who routinely photograph deep in the jungles with rain and blood spattering your cameras hither and yon). And, built in image stabilization. That's about it. The sensor is already there. A full two stops better noise performance (by some accounts) than the EP3 at higher ISOs. But I picked one up, with the 14-42mm zoom lens for a bit under $600. Turn key. All done. No waiting list. No fuss.

Without a doubt the OM-D will trample the G3 when it comes to body construction and design. It's in a whole different bling class than the plastic-over-aluminum frame construction of the G3. There's no way to stick a battery grip on the G3 (that I know of) and the jpeg colors of the OM-D will probably take the G3 to school. But....it's a great sensor and a great implementation of controls and it's cheap. I've had one for a couple days but yesterday was the first day I had a few spare hours to go downtown and give the G3 a run through. So let me give you my opinion. And remember, this is all about my impressions. We don't do technical tests here at the VSL secret, underground labs. Our massively parallel supercomputing nest is dedicated to data mining the epicenters of creativity. We can't allocate computing resources for something you can easily discern with your eyes and your hands (haptics rears its beautiful head....).

But, in fact, I have come to praise the G3, not to bury it. I'll admit that I don't keep up with every camera announcement from every camera manufacturer. I had the prejudice that Panasonic made cameras in only two m4:3 flavors: The button and dial laden, professional GH2 with its EVF and then a slew of smaller, less capable cameras with only LCD screens on the back and the option of adding a vastly inferior EVF. At least that's what I saw the last time I took a look.

But, when I finally focused on the relatively new line of cameras Panasonic had on the market I saw I was mistaken. The G3 is reviewed to have better noise performance by a small amount, than the GH2. The AF system samples at 120 Hz just like the EP3 so the performance is comparable. The EVF has similar specs to the current state of the art in the Olympus segment. And, while the G3 body, with its limited supply of external controls, takes a bit of time to get used to I can see that the menu driven touch screen is viable and, in most cases fast to use.

When we talk about contrast detection auto focus a prime variable in the overall performance equation is the sampling rate which is driven to some extent by the speed/throughput of the processing sensor. The AF motor moves the lens through the range of distance until it find the peak of contrast in the scene you've put in front of its sensor. It must repeatedly sample and shift and then sample and shift until it isolates the setting that gives the highest level of contrast. Within the sampling are latency periods where, once sampled the information must be processed and compared. Reducing the time of the latency periods and increasing the frequency of the sampling are the two ways to increase the speed of the system. The GH2 and the G3 were first to increase the sampling speeds from 60 Hz to 120 Hz (they both use the same "Venus" processor). The EP3 also adapted that strategy and added optimized lenses in order to further increase the speed and allow them to boast of having the ultimate AF speed amongst mirrorless cameras. The new OM-D AF seems to be based around increasing the sampling performance of the AF circuitry to 240 Hz. Whether or not we'll see improvements in lenses that are not optimized for the new processor initiative remains to be seen. But today, right now, the EP3, the GH2 and the G3, in good lighting conditions, are all just as fast as I need them to be and they are more accurate with higher speed (bigger aperture) lenses than their DSLR brethren.

I have not used the G3 in any configuration other than raw format and I haven't used it yet with any other lens than the 14-42mm kit lens that came packaged with the body. The lens seems to do a good job with most close up scenes but when I look at my building shots at 100% I see a little softness as we get into near infinity focus. That's easy to fix. You just put on a better lens. The 14-42 kit lens doesn't seem to garner many kudos and yet, for around $125 with built in IS I think it's a good value. Especially for routine, close-to-mid distance shots. I'll spend some time with the camera and the Panasonic/Leica 25mm 1.4 Summilux in the next few days and I think that should make a huge difference in overall quality. Even so, in the samples I have here I'm not disappointed. On screen the 16 megapixels are sharp and the noise at everything I shot under ISO 800 is non existent.

There are two things about the G3 that I didn't think I'd like. I was wrong. Serves me right for pre-judging. The first is that the camera doesn't have the dandy automatic switching between the EVF and the LCD (cost savings concern, no doubt). You have to do it manually, with a button. But that's fine with me because I want to use the EVF for everything except final review and menu setting. I don't want the screens to swap every time my hand moves past the little sensor. Especially when mounted on the tripod in the studio. Panasonic engineers are smart though. You can set a menu setting so that when you hit the "play" button to review what you've shot the camera automatically switches to the LCD. There when you need it but not switching when you don't. I prefer it this way. Thank goodness for cost saving measures.

The second thing I was prepared to dislike was the touchscreen interface. But I ended up liking it a lot. Mostly because it's user programmable. You get to choose the five different menu items you most use and you put them on the screen. I chose ISO, focus settings, WB, file formats, and exposure compensation. Now, to use any of these settings all I have to do is hit the "Q" menu button and directly access the menu item on the screen. The screen is pressure sensitive rather than capacitance sensitive. It has positive feedback. This is quick and easy and you can program whatever controls you use most often.

So, if you add it all up it's a pretty convincing little camera. Detractions? The styling is a bit pedestrian. The lack of IS bothers me when I think about using prime lenses with no built in IS, and the body feels a plasticky. But you have to consider the other side of the equation. For about half the price of the announced, but not available, OM-D you get a camera with a sensor that's probably very close to what will be in the OM-D and, for all practical purposes will be very close in raw performance. You get a fast focusing camera. Maybe not as fast as the new Olympus when the Olympus is coupled with the state of the art lenses but almost certainly in the same league with most of the existing lenses. You get a fun and more flexible implementation of the touch screen technology and that makes this camera interesting to me and the people who are looking for straight out performance over additional features.

But it all goes back to one of my basic premises: Most modern cameras are really damn good. If your technique is good and you learn the interfaces you should be able to get almost indistinguishable files from all of them. The lowest common denominator will be generally be your user chops and the level of interest inherent in your subjects. I am currently using the GH2 in manual mode for a lot of my studio work and I'm happy with its on-the-final-screen performance. The G3 makes me re-think my lust for the newer cameras. Could it be that Panasonic had the level of sensor performance last year that we're waiting for from Olympus with bated breath this year? Is the AF performance on the G3 almost comparable? Aren't they all in the same family? Won't all the lenses work interchangeably?

I don't have any doubt that the new OM-D will have features that makes it more desirable than the older Panasonic G3. I want in-body IS. I like the idea that it will be the best IS in the history of the galaxy. Almost as good as my old tripod!!! And I'm sure that the Jpeg color engine will be the industry leader. Finally, there are a legion of people who are crying out for weather proofing. I have to say that I've yet to lose a camera to rain or dust but I've only been shooting for a few decades. I'm sure other people have experienced camera failures as a result of exposure. I'm a disciple of the Ziploc bag religion of camera protection but I fully acknowledge the right to exist of weatherproofarians no matter how extreme I find their belief systems. The Olympus will be a nice package. In the way that a BMW is an upgrade to a Honda. But, like the car analogy, there will be some who want the sensor and AF performance who don't have the budget for the premier offering. If they don't need built-in Ziploc Bagging, and they can live with the AF that comes resident on some of Panasonic's better lenses, and they can live with the stigma of a "lesser" model, they may find the absolute performance to be pretty much the same.

What a terrible realization for me to present you with on President's Day. I thought we had the whole m4:3rds thing all figured out. The OM-D was to be the Holy Grail of little cameras and we would all be happy and content once we acquired one. Funny how the market works and funnier still how my vision narrows close to launch dates and expands again while I'm awaiting delivery. Once again the G3 serves to remind me that we've all been here before. We're always hopeful about the silver bullet that will take our art to the next level only to find that all it delivers is photographs with a little bit more detail, a little bit faster focus and a little bit steadier steadiness. In this case perhaps no more resolution than what we can get right now, not much more high ISO noise reduction than we get right now and AF that is marginally faster for a handful of new lenses that we don't yet own. Our consolation? The new camera is very nice to look at and feels very nicely balanced in our hands. We hope.

The bottom line? I don't know that there is a bottom line. The camera world is a chaotic place with little camps swirling around banners. In one corner we have the full frame 35mm high res contingent for whom everything hinges on ultimate resolution and sharpness. We have, of course, our micro four thirds camp where we look to blend high performance with high usability and high portability (after all, what good is all the gear if it's too cumbersome to carry?). We have the pilgrims of nose bleed performance who have knotted the ropes of high intention around their photo vest frocks and set out into the desert in pursuit of the mysteries of medium format, and we have the legions of people traipsing around willy-nilly with their iPhones snapping a glorious quantity of interesting frames and then shoving them through the kaleidoscopic blender to make them more.....appealing.

I've been beaten over the head with the idea that there is no "right or wrong." That all approaches are worthy and equal. That there's an equivalence of sorts whether you use an 8x10 inch film camera or your happy-snappy phone to create your images. While I tend to veer toward a more defined philosophy where effort has value and is integral to the process I won't confuse things by arguing that today.

Where I will comment is on the performance of Olympus' promotional machinery. Well done, marketers. In a short amount of time you created a tremendous amount of buzz, filed us with desire we barely knew we had, deflected our attention away from similar products and got us all excited. If the product they deliver does everything they say it will be a monumental success, and, no doubt, it will be a hell of a lot of fun to shoot with.

The G3 is no OM-D but it's a hell of a lot closer than a lot of people might like to believe. I think I'll go out and shoot with mine again today. After all, it's already in my hands.

2.19.2012

Ah. The thrill of getting to market the book you worked on...

Ever patient Jana sits for a portrait under the saucy glow of an LED fixture.

The image at the top came from some permutation of this main lighting set up.

That's me in the small studio, directing Jana, thinking about the writing and thinking far

ahead about marketing the book.

I bet just writing books about photography is fun. Writing the books sounds like an easy thing to do. But now, in the 21st century, the authors of books on various aspects of photography have to do much more than "just" write. The Syl Arenas and Kirk Tucks and Neil Van Niekirks, and a legion of other photography book impressarios, have to wear many hats. We research and write, just as authors have done since the dawn of non-fictional literary time, but now we are on the receiving end of a whole new roster of responsibilities. For me, illustrating the books with hundreds of photographs is the most time and resource consuming part of the project.

In total opposition to the way my brain is wired (I like chance more than planning) I must now think about what I've written and translate the verbal "score" into a "before" and an "after" images. I must jettison the fluidity I've acquired through decades of nearly autonomic practice and now think in terms of discreet and obvious steps so I can lead the non verbally disposed book owners through each painful step of concept. It's like doing a picture book for the resistant to reading and a real book for the totally verbally oriented at the same time. And it takes the two sides of the brain that are the furthest from each other to do reasonably well.

I must recruit models who are patient enough to work with me in this whole step by step miasma and quel their expectations. We'll be turning out examples, not art. I must make sure that the models fit a modern idiom of culturally acceptable physical beauty and yet remain accessible. I try to keep it fun for the small crew involved. Our advance money only covers payments to the models and to my assistant. There's nothing left over for travel or gear or even a make-up person.

Once the images are in the bag I need to go in and do minor retouching of things like fly-away hairs and stray threads to pre-empt the vacuous critiques of people who are obsessed with finding flaws. If a model's face shows too much texture I am accused of not knowing how to light said model correctly. If the model has flawless skin I am accused of massive retouching to cover some perceived lack of technical capability or, better yet, to call into question the efficacy of the basic premise I am trying to prove in the book.

Once the words are written, the images taken and corrected and every image spread-sheeted to match some arbitrary position in the text I can begin the unfortunate process of sketching out "lighting diagrams" so that people who can't understand the copy and can't extrapolate the lighting design from the supplied "behind the scenes" shots supplied can make enlarged copies of the "lighting diagrams" and paste them on the floor to follow without regard for the vagaries of their alternate spaces and gear. As though the exact placement somehow trumps the basic idea of the lighting.

The final run through the Aegean stables is the writing of captions. Captions seem to be for the people who either despise reading the body copy and are hoping for a micro "Cliff Notes" approach to book reading or for the people who are confused by the images and need yet another layer of guidance. But then captions are also like candy and most of us crave them in spite of ourselves.

If you are a slow writer or a slow photographer or both, this process can grind on for the better part of half a year. If you had nothing else to do and didn't need to support yourself or your family you could probably finish your book project in the better part of a month. Then it leaves your hands and goes off to your publisher and you relinquish a certain part of control that gives you the illusion of perfectionism that's never really there. My most recent book went through several steps of proofreading and yet there are still words that didn't get bonkled or trogmolated into the right spelling. Spell check is to proof reading as Facebook is to real relationships....

And then there's the process of color correction. When images make the leap from monitor to CMYK offset process printing there are things that can change. Colors can slide from intention to obfuscation. From proof to prank. From veracity to vexing.

I never saw color proofs for the LED book and while the large majority of images are right on the money there are a handful that are too dark and an even smaller handful (several fingers full....) that have unfortunate color casts. I say unfortunate because I was trying, in this particular book (the one on LEDs) to prove that the lights in question had come of age. That, with good practice, a photographer could make color rich and color accurate images with the current offerings of midrange and better LED fixtures.

Most readers will look at the majority of images contained in the book and get the message. But I've already had one reviewer jump to the conclusion, based on a small minority of mis-printed images, that the LEDs are at fault, ergo my premise is faulty and, QED, the book is without merit. Oh the slings and arrows of outrageous (mis)fortune... My very integrity sacrificed by a printer's interpretation of color and density.

So, at this point the writer/photographer/production drone is done with his part of the project and the book is launched and the big dollars start pouring in. Right? Ha, Ha, Ha, Ha, Ha......

Here's where the modern photographer/writer hits the wall of 20th century mythos and, submerged in bathos, comes to the queasy conclusion that his book will die on the vine without Promethean efforts of marketing. Every week dozens of printed and e-published books on photography are unleashed onto the market. And there is both a limited demographic market, and within that demographic, a limited budget for books. For a book to do well it must be marketed. If I could afford to take out a full page in the New York Times Sunday Magazine to show off the book, and couple that with a few appearances on Oprah, and some live interviews on the splash page of DPReview.com I could sell a prodigious number of books in a flash. But reality is based on projected returns and a host of other unknowns on a mysterious matrix. And the reality that niches get smaller as topics get progressively more arcane.

Publishers run press releases in all the usual places and take the book (along with dozens and dozens of others) to the trade shows. But the real market place is Amazon. And to move the numbers in your favor on Amazon the writer/photographer is encouraged by the publishers and, if he wants the books to return any cash at all, is self-motivated to cast off the hat of creator and don on the plaid sportcoat and winning smile of the marketer/salesman. A role for which most creative people are profoundly unsuited.

We are encouraged, externally and "internally" to blog about our new book, to do as many book signings as we can, and to reach out to every point on our friendship/acquaintance compass and flog the book. I'm putting together a book signing at Precision Camera for next Monday. I hope I am perceived as smart and warm and effusive and deeply interested in the continuing education of my peers and the hosts of hobbyists that make up my implied constituency. I hope no one wants to argue (using technical info from 1990) that LEDs are incapable of even lighting up a computer screen. Much less a portrait shoot. (Everyone does realize that LEDs are used in your new flat screen TVs and in the latest computer screens and they seem pretty accurate....right?)

And I'll do the same stand-up routine for any club, group of class that will have me. But why? Why do photographers feel compelled to write books in the first place? I'll have to be honest. Several publishers have told me the same thing and, even though it pains me a great deal to admit it, it's the same basic logic that has been espoused by Seth Godin for as long as he's been espousing. To wit: You won't make any real money writing a physical book. The book is a souvenir for an event (according to Seth). People come to see you talk about something and the book is the take away. Like buying something fun in the gift shop of a museum after you see the King Tut exhibit. The publishers sell it like this: "You'll gain credibility with your market so that you can better sell your workshops and seminars."

Well, that's all well and good but what if you don't really want to do workshops and seminars? I should have thought that through sooner. The math is simple. You write a book for a publisher and you get a percentage of the cover price in return for that six months of your life you spent hunched over a keyboard or cajoling models. If you were a best selling fiction writer with a large fan base you might see hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of royalties in a short amount of time. If you are like most fiction writers your book will sell fewer volumes than it takes to pay off your advance. Your book will be remaindered in a season or two and you'll have the opportunity to buy the surplus stock from your publisher at some sort of price that covers his cost of printing. Salvage value. You will have worked for years on your novel for a few thousand dollars.

A photo book writer who does a great job marketing his book might sell 5,000 copies in a good year. A book that really hits, by a star writer in our field (sounds like "Shelby"....) will make many multiples more. But most of the books will depend on the "long tail" of photo books to return profitability to the publisher and, to a lesser extent, to the creator. A book with a great "long tail" is LIght, Science and Magic because it's well written and the knowledge it teaches doesn't change or go in and out of style.

If I work on marketing the LED book as though it was my full time job for the rest of the year we might be lucky enough to sell 5,000 copies. Maybe. Figure that the royalties will equal about one full week (maybe two weeks in the current economy) of work in my "real" job as an advertising and corporate photographer. In order to have the book make economic sense I'll have to leverage its "first to market" implied expertise to launch an aggressively marketed series of cutting edge workshops about LED lighting, complete with hot models and stops in too many second tier markets to mention. Coupled with some sold out houses in some big metro markets. Hello Carnegie Hall !!!!

But the fly in the ointment is this: I'm no great orator like David Hobby. I can't hold an audience in my hands, with them waiting for the next utterance about luminance, like he does. I'm no Scott Kelby with his joie de vivre and his witty patter, standing in front of legions of people who are desperate to understand the vagaries of Photoshop or the menus of their cameras. I'm just a guy who likes to write and take pictures and who never thought he'd be held captive to the back end of the publishing process. A self imposed voluntary, involuntary servitude of creating an informercial-esque circus around a straightforward book.

I'd rather keep writing and photographing. It's sunny and warm here now. I'm abandoning all marketing efforts for today and heading out with my camera and a smile on my face. The book market can wait.

And, by the way, we are having a book signing and "meet and greet" on February 27th, from 5 to 7 pm at Precision Camera here in Austin. I'm sure you'll want fly in for it....

2.17.2012

A nostalgic look back at one of the great, early, digital cameras. The Olympus e-10.

I was at Precision Camera several times this week doing the kind of things that drive more level headed photographers and IT professionals slightly crazy. I was buying more micro four thirds stuff, getting rid of the little Nikon V1 System and trimming down some of the Canon inventory. What shall we tackle first? How about the m4/3rds? It's no secret that I really like EVFs and I really like small and light cameras. I'm waiting impatiently for the OM-D but in the interim I stumbled into the Panasonic G3, liked what I saw and read (I blame Michael Reichman's review from last Summer the most) and decided to pick one up. A fun camera for less than $600 bucks and maybe the current champion for lower noise ISO among the m4:3rds camp. I've enjoyed the way the Panasonic GH2 works and I've used it now on six paying jobs this year, to my delight and to the satisfaction of my clients.

The G3 plays well with the Panasonic/Leica 25 Summilux and the 45mm 1.8 Olympus lens but, albeit, without IS. The files are crisp and detailed and the noise, up to 1600 ISO is very normal. And very workable.

The Nikon is a glorious little system and I'm sure I'll regret consigning it the minute it sells. Which will probably be the day before Nikon comes out with a gold-banded, 18mm f1.4 (50mm equiv.) prime lens. But I got tired of waiting for faster glass and more and more captivated by the fast lenses that Olympus and Panasonic already had on tap. Waiting for me. Taunting me.

Something had to go. And the Nikon got the nod. It failed the "eternal" test. That's the test that gauges how much you carry around your system, over time. More and more I left it at home and took faster glass. I'm a creature of some habits even if I'm not brand loyal. In the grand number scheme of the "eternal" test the current winner is the EP-3 which I've carried most days since purchase. More than the Canons and more than the V1. Even more than the GH2 (which is currently in second place for fun shooting and in first place for commercial shooting, just slightly ahead of the Canon 1DS mk2.

Before people melt down let me quickly say that I really like the Nikon system and it has its unique attributes but I finally just ran out of bandwidth.

I had too many Canon 1D bodies so one of them got donated to an up and coming young artist who will remain anonymous. We've winnowed it down now, in the Canon camp, from six cameras at the start of the year to three. And we may get even tighter on the "dinosaur" camera inventory as the m4:3 becomes more compelling. But I need to at least keep the two remaining, full frame bodies around for those moments when only the slightest sliver of Zeiss focus will sate my imperious "bokeh lust."

But, I started this whole article off intending to talk about an Olympus camera that I consider to be their Sputnik of digital cameras. Their moon launch. The incredibly nice piece of alloy and glass that put them on the digital map in 1999. Yes. I'm talking about the supernaturally incredible e-10.

It solved so many problems. Let me set the stage: Digital was in it's infancy. The only affordable, professional digital camera on the market was the Nikon D1 and just between you and me it was an unqualified piece of shit. The files were all over the map and it made a joke out of the idea of controlled flash. Not to mention that it had a buy-in price of over $5,000 and a noisy file that came flying off a strange 2.7 megapixel sensor. Banding, noise and wild flash exposure inaccuracies were included at no charge.

Later in the year Olympus announced, and shortly thereafter delivered, the e10. A four megapixel camera that featured a permanently attached 28-140 zoom lens filled with ED and Aspherical glass. The files were beautiful and, at ISO 80, 100 and 200, stomped all over the big Nikon. You could get a battery grip with a mondo battery that would last for hundreds and hundreds of frames. True all day shooting. The Nikon? Better have been prepared with one battery for every 100 frames.

At any rate I have the fondest memories of the e10 and carted it to Europe and Miami and Hawaii on corporate shoots, most times in tandem with a Hasselblad film system. That was the nature of the non-linear digital adaptation. I had forgotten about the camera until I came upon an old CD with these images of Christa. We shot them for a tony furniture store back in 2000. Shoot with monolight flashes and careful metering. The images were used in magazine and newspaper ads and on the web.

While I"m happy with the color and sharpness the 4 megapixel files do show their limitations when I splash em big across the monitor and ramp it all up to 100 %. It's not that the quality is bad by any stretch of the imagination, the files just run out of information. But the Olympus people figured out color and good optics way back then.

Now my little Panasonic cameras will do 16 megapixels and the new Olympus should match them. We can shoot at higher ISOs but I would hardly need to in a shoot like this. Remember, we're creating the light not just ramping up random photons. The e10 had its problems. Biggest of which was a tiny buffer. But this job and scores like it made this camera the most profitable digital camera I've probably owned. In fact, we did all the executive headshots for one of the world's largest computer makers for two years solid with this camera and it never let us down. I sold it to buy a Fuji S2. But that's a whole other story...

So, where am I going with all these m4:3 cameras and lenses? I'm on a journey. I'm heading back to the fun zone of photography. It's in a different part of the geography of photography from the earnest pixel measuring maniacs. Far, far from the perfection seeking "professional," DXO approved tools of the serious and ponderous. I'm hedging a bit with the Canons but the momentum.......is somewhere else.

2.15.2012

Of Course It's Better. It's Bigger. Altogether now, "Supersize Me."

Ben. Photographed with a Leaf 40 megapixel camera

and a wickedly cool Schneider lens.

Can you feel it as it crashes against the shore? A wave of camera rationalization that's just amazing. Driven by the desire to differentiate the work of photographers who want to make money from those who just want to be photographers. A new approach that provides a new set of reasons for clients to hire photographers who'd like to make a real living doing this stuff, the lure of medium format digital cameras. And the new crop of maxi-pixel Nikons and Canons (believe me, they're coming).

Will it work? For some. Will it fail? For some. I've played with the "big boy" cameras. They didn't make my work better or worse. Had I kept them they would have made more cost of doing business rise appreciably. Here's the deal: If you are already working for the big time clients you'd like to be working for you probably didn't need the big medium format camera you just bought, anyway. The clients came to you because they already liked the way you do stuff. The camera gives you a new anchor to try to hold them to you but deep down you know you're held captive by the capriciousness of styles in the advertising coliseums. And if the clients you wish you worked for aren't already returning your calls then just showing up with new hand metal isn't going to convince them that you just became an artist.

When I look at the portrait above the first thing I notice is not the pixel count because we've downsized it for the web. The first thing I see is the expression. The direct connection with his eyes. His self-assurance. If the first thing you noticed was some expression of dynamic range (remember, we're looking at 6 or 8 bit monitors and we're looking at 8 bit compressed jpegs here....) then I haven't done the job of bringing direction or feeling to the image.

When I hear people talk about the NEED for more pixels and more dynamic range and more bits I think of this image below:

Brio. For Time Warner.

If you listen to the howling masses today you'd think nothing could be accomplished, photographically, with fewer than 16 or 18 megapixels. But we did the image above with a Nikon D100. A whopping six megapixels. A four frame raw buffer. Molasses slow CF cards. But the light is good and the expression is good and the ads worked and the check cleared. And I'm not really sure if the image would have looked better in newsprint at a higher pixel count.....

I think we tend to lose track of what we really need in the emotional flurry of the new camera announcements. I felt excited when I first talked to the Olympus reps about the new OM-D. I really had a desire to snap one right up. But I shot with my little Pen EP-3 today when I looked at the files I saw a camera that was outperforming my Nikon D2sx from four years ago. I saw detailed files with perfect color. And I chuckled to myself when I was reminded by the client that our destination ( along with 60% of marketing work these days ) for the portrait I was shooting would be on the company's website. Last time I checked the portraits were running about 320 by 320 pixels. Would we be able to pull it off??? Or would we NEED the power and the glory of a Phase One?

I've used a lot of cameras. My readers will attest to that. And I like almost every one I've held in my hands. But they're interchangeable. From six megapixels to forty megapixels, none of the specs really matter if I can't make someone genuinely smile and if I can't have them engage the camera in a collaborative and self assured way. And if I do that part of my job right then just about any camera I can clutch in my hands will probably deliver a serviceable file.

It's more fun to shoot with the latest stuff. But it's hardly necessary.

The portrait I shot today was fun not just because the subject was fun and knowledgeable and personable. And it wasn't fun just because it went well and the images looked good. It was fun because I did it on a camera that many people think isn't suited for professional work, with lights (LEDs) that people still don't get. At the most we were using less than $2,000 worth of gear. And it was fun because the success or failure of our undertaking didn't depend on the gear. It depended on me doing things correctly and the sitter joining in with the spirit of the engagement. And that's why this business is fun. Not because we can bring "the big guns to bear."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)